.

If you have any comments, observations, or questions about what you read here, remember you can always Contact Me

All content included on this site such as text, graphics and images is protected by U.S and international copyright law.

The compilation of all content on this site is the exclusive property of the site copyright holder.

About Buckwheat, A Program at Bouman Stickney Farmstead Museum

Sunday, 3 November 2019

The description of November's program at the Bouman Stickney Farmstead Museum really interested me. "Buckwheat from the Fields to the Table: Buckwheat, an ancient grain, was introduced into Colonial America by the earliest colonists including the Dutch. Susan McLellan Plaisted will demonstrate how these early farmers, such as the original owners of the Bouman-Stickney Farmstead, would have grown and milled buckwheat. This hands-on program involves grinding and sieving buckwheat flour as well as preparing buckwheat cakes for the open hearth."

I like buckwheat, have cooked with it, have a friend who grows it.

Here's what I know. But I wanted to hear what Susan would share.

My friend Janet has a wonderful vegetable garden. She grows buckwheat as a green manure. It has a short, rapid growing period of only 10 to 12 weeks. Turned under the soil to rot, it adds nitrogen to the soil, improving the fertility after "hungry" crops such as corn have been cultivated. Janet also grows the buckwheat for the bees in the hives that her husband keeps.

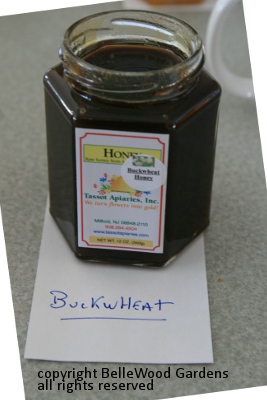

Pure buckwheat honey is dark and very flavorful.

Kasha varnishkes is a porridge that combines buckwheat with pasta. I like to use the tiny farfallini, little bowtie pasta. These were the ingredients for an upmarket recipe in The Gefilte Variations that includes mushroom, onion, and eggplant. But the basics are the same - toss one cup of buckwheat groats with a beaten egg. Cook in a dry pan, turning and tossing constantly for 2 to 3 minutes until the groats are dry and separated. Add 2 cups of hot broth and cook at a simmer, covered, for about 10 minutes or until done. Add the cooked pasta. Then serve. Kasha is really Russian for porridge, but here and now we use it to mean buckwheat.

Japan has a very different cuisine, using buckwheat for noodles. Soba noodles are easy to find in Asian markets. I prefer those made only with buckwheat, but buckwheat with wheat flour soba noodles are also available.

You should make a note: wheat contains gluten, which buckwheat does not. Leavened products need gluten to aid in rising. Even blini, thin little crepes, often have some wheat flour in with the buckwheat in the recipe.

Now, on to the Bouman Stickney Farmstead Museum and thir program about buckwheat.

Buckwheat has nothing to do with wheat. It isn't even a grass. Closer relatives are sorrel, knotweed, and rhubarb. Since its seeds have culinary uses the same as cereals, buckwheat is referred to as a pseudocereal. With the adoption of nitrogen fertilizer that increased the productivity of other staples such as corn and wheat, the cultivation of buckwheat grain declined sharply in the 20th century. However, with the increasing interest in gluten-free food it is again increasing in popularity.

"Boughten" buckwheat flour is pale in color and uniform in texture.

A big advantage of buckwheat, back in the 18th century, was that it could be

ground at home. So easy a child could do it! No need to travel to a miller, who

kept a portion of the ground corn or wheat flour in payment for his services.

Today we used a small mortar and pestle. On a farm, they'd use a quern-stone.

Once we ground the buckwheat it needs to be sifted, to remove fragments

of the hulls. Today we used two different sieves, of successive fineness.

And here's the result - freshly ground and neatly sieved buckwheat flour.

Susan is making a very simple receipt, adding a little salt (we pounded

very coarse salt in a wooden goblet with a wooden pestle), a beaten egg,

and water to the buckwheat flour. Susan did make it special by adding

some nutmeg, which we also ground fresh. So aromatic, freshly ground.

Next, Susan makes a burner by shoveling red hot coals onto the hearth.

She gives the batter its final stir, all the while telling us what and why she's doing.

She checks the consistency by dropping a spoonful back into the bowl. It must be soft,

but still hold its shape, not spread and run all over the griddle when it is being cooked.

The little buckwheat cakes are spooned onto the griddle, a dollop at a time.

They quickly brown on one side, then turned to brown on the other side.

These buckwheat cakes are plain fare, even with the grated nutmeg. Susan brought some apple butter she'd made, with which we can embellish our samples. In the 18th century, the buckwheat cakes would be served in place of bread to accompany pottage.

Interesting, but I think I'll stay with kasha varnishkes.

Back to Top

Back to November 2019

Back to the main Diary Page